Together we stand: TIMES Researchers discuss the education of collaboration

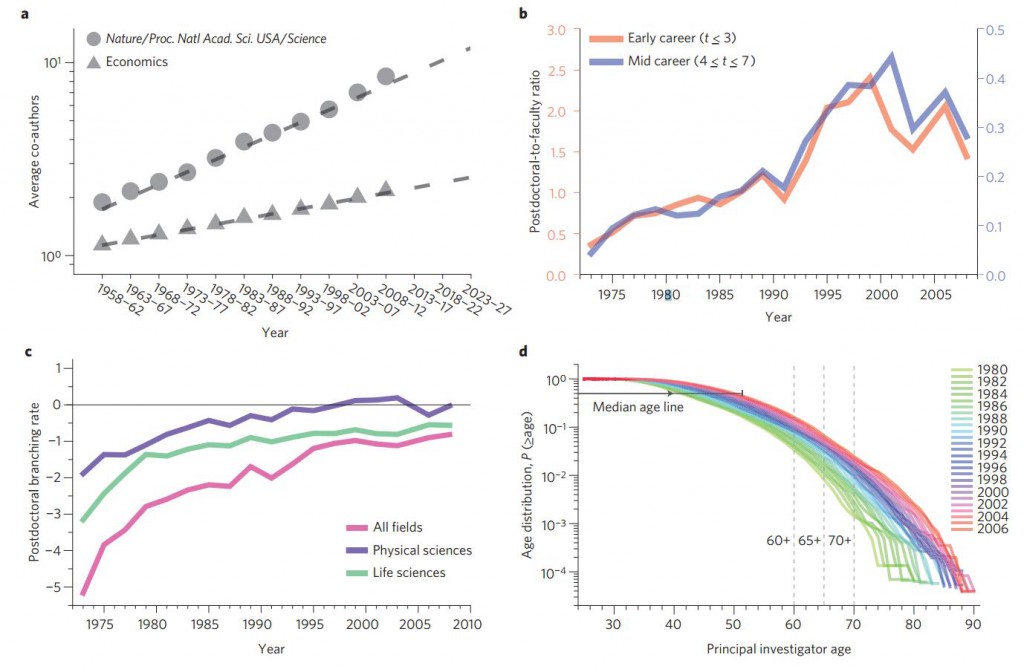

Harmony among scientific researchers is not a new concept. For over 70 years the structure of scientific research has transformed from a series of solo endeavors to a more collaborative model. Studies like The Manhattan Project and Higgs boson experiments illustrate the move toward a team scenario. The question remains, is the current state of academic training supporting this trend?

According to an article in this month’s Nature Physics published by TIMES researchers Ioannis Pavlidis and Ioanna Semendeferi, in collaboration with Alexander M. Petersen from the IMT Lucca Institute for Advanced Studies, a shift in the structure of graduate education and research is necessary to further develop this model.

“Science is no more the work of ‘solo genius,’ but the product of a collective operation, involving hundreds or thousands of scientists at a time,” Pavlidis said. “The recent discovery of the Higgs particle, for instance, took more than 3,000 scientists working together. We live in the era of team science where groups of scientists resemble ant colonies.”

Pavlidis, Semendeferi, and Petersen argue that while science and research continue to thrive in a collaborative environment, the academic career advancement of a scientist is based solely on their own individual recognition. While many may work on one particular grant together, in the current system generally only one person is recognized as a Principal Investigator, or PI.

The solution? An examination of the film industry, for starters.

“A good example is in the role of film editor,” Pavlidis said. “There are clear avenues for independent recognition with an Oscar in film editing, for instance, and the work is not simply a step along the path to directorship. The same applies for scriptwriters and sound engineers, as well as almost every role in the filmmaking process.”

The team suggests a restructuring of roles within research grants. Rather than continue with the current lone-PI arrangement, a move toward a “crew structure” is recommended, in which multiple investigators work together with equal footing. This, along with a reformed grant overhead structure in which more tenure-track positions are funded and opportunities are greater for postdoctoral individuals to move up within the ranks, as well as rebalancing teaching loads and creating late career options for faculty, can cultivate the change needed to support the continuation of cross-disciplinary collaboration in science.

Additional information about this work can be found on the UH Science Ethics website. The article has also received recognition by Science Daily, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and ABC 13 Eyewitness News.